Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) play a pivotal role in addressing the global climate finance gap, providing over half of global public climate finance—amounting to €335 billion annually in 2021–22. A new report by the Climate Bonds Initiative, ‘The Role of Development Finance Institutions in Accelerating the Mobilisation of Green Capital’, highlights the untapped potential of European DFIs to mobilise private capital and significantly enhance climate investment.

The report examines the efforts of 23 European DFIs, including 14 members of the Association of European DFIs (EDFI), to channel private capital toward sustainable economic development in low- and middle-income countries. Despite their critical role, current mobilisation levels are insufficient to address the growing climate investment gap. Doubling current best mobilisation efforts could raise DFI contributions to €740 billion annually, making a substantial dent in the global climate finance needs, which currently stand at over €1 trillion per year.

The report reveals stark disparities in mobilisation performance among DFIs. In 2022, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the European Investment Bank (EIB) achieved mobilisation levels of only 20% and 15% of their respective balance sheet sizes, while EDFI members mobilised a mere 1% cumulatively. If all 23 European DFIs matched current best practices, they could collectively mobilise €370 billion annually, with potential to double that to €740 billion.

Although DFIs often set climate targets, only 37% have specific mobilisation targets, and these are rarely linked to climate objectives. The absence of transparent reporting and clear targets weakens incentives to crowd in private investment, limiting DFIs’ impact on climate finance.

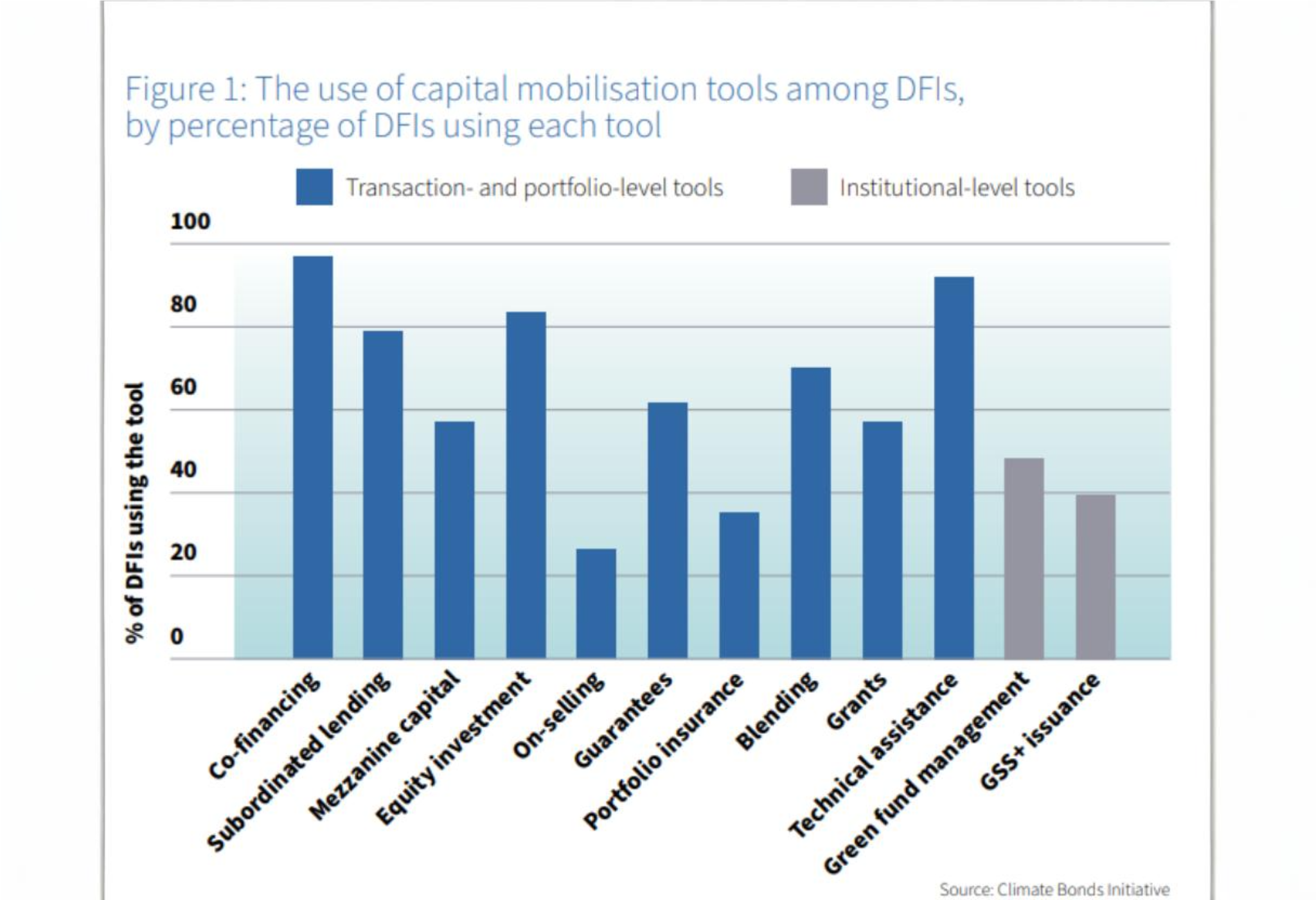

Several systemic challenges hinder effective mobilisation. DFIs often rely on transaction-specific mobilisation tools, which have higher costs and lower scalability compared to institutional-level approaches. This limits the use of innovative tools capable of mobilising capital at scale. Also, inadequate reporting on investment performance, including default and recovery rates, deters private investors from participating in DFI-led deals, especially in unfamiliar climate projects.

The report also points out that green bonds, a critical tool for climate finance, account for only 17% of DFI liabilities on average, despite significant alignment with green frameworks. Additionally, minimal issuance in local currencies limits market stimulation and currency risk mitigation. Additionally, only 26% of DFIs strategically use on-selling for equity investments, restricting capital recycling and private investor engagement in later-stage climate projects.

Most climate investment needs lie in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), which face worsening financial conditions, currency depreciation risks, and growing climate vulnerabilities. DFIs, tasked with operating in riskier environments, must enhance risk-sharing mechanisms to address these challenges. However, regulatory and policy barriers, coupled with limited shareholder action, constrain their ability to take on greater risks.

Definitional inconsistencies for climate investments further complicate DFI operations. The MDB Joint Principles for Paris Alignment lack granularity, while the EU Taxonomy’s limited scope and references to EU legislation create barriers for non-EU investments. DFIs must adapt their frameworks to better match investor expectations and available information.

To maximise their impact, DFIs must adopt more ambitious mobilisation targets linked to climate goals, improve transparency in reporting, and broaden the range of tools used to attract private investment. By strategically addressing systemic barriers, DFIs can unlock significant private capital to bridge the climate finance gap and drive sustainable development globally.