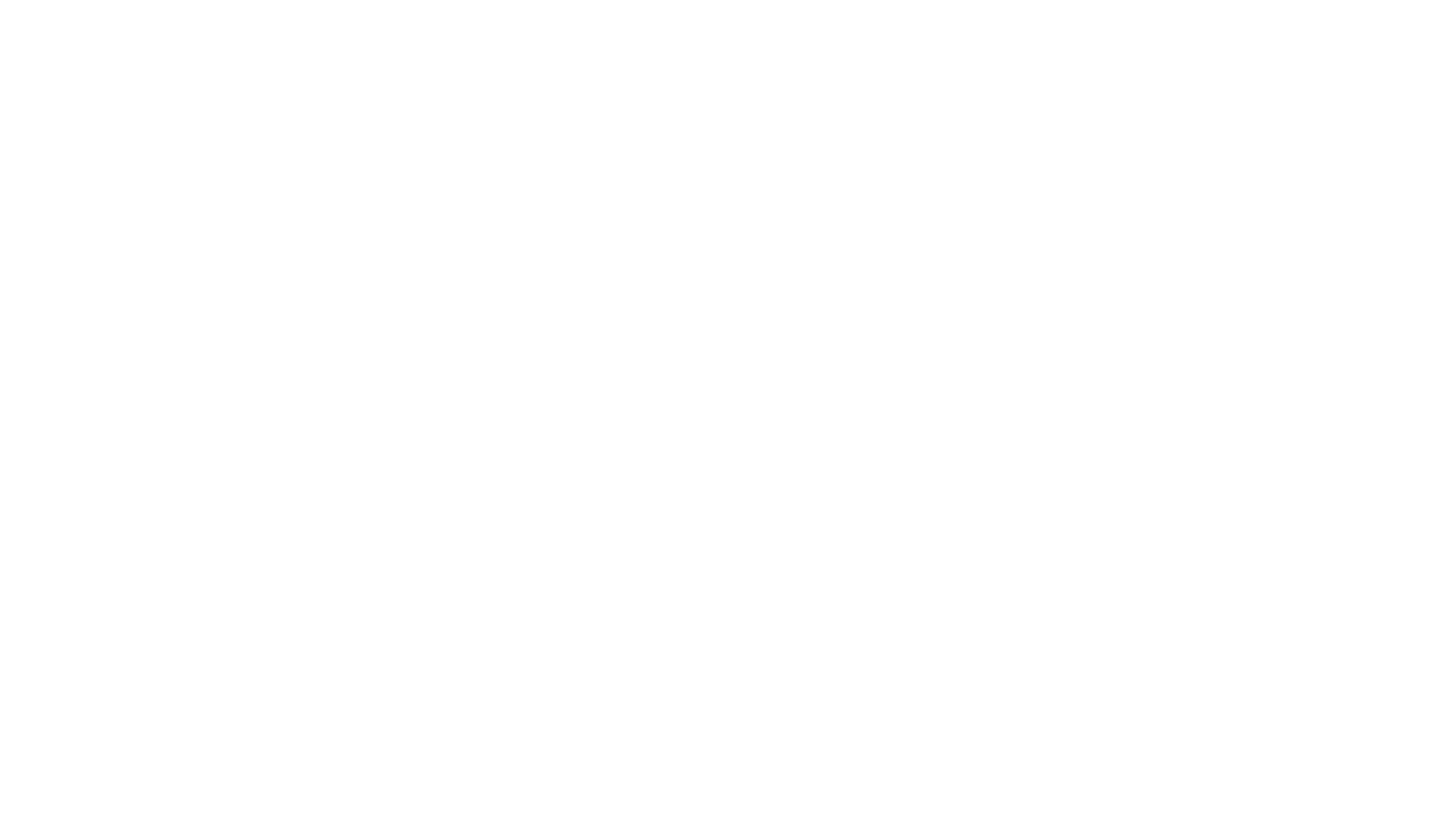

Corruption is worsening worldwide, with even long-established democracies registering declining performance, according to Transparency International’s 2025 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), published on Tuesday (10 February).

The annual index shows a sharp erosion at the top end of the scale, with the number of countries scoring above 80 falling from 12 a decade ago to just five this year. Transparency International warned that weakening political leadership and shrinking civic space are undermining global anti-corruption efforts.

Democracies, which traditionally outperform autocracies and flawed systems on corruption control, are among those showing worrying declines. Countries including the United States (64), Canada (75), New Zealand (81), the United Kingdom (70), France (66) and Sweden (80) all recorded weaker results. Since 2012, 36 of the 50 countries with significant CPI score declines have also seen reductions in freedoms of expression, association and assembly.

The report highlights a rise in anti-corruption protests led by Gen Z in 2025, particularly in lower-scoring countries where progress has stalled or reversed. Young people in countries such as Nepal (34) and Madagascar (25) mobilised against the abuse of power and poor delivery of public services and economic opportunity.

Transparency International cautioned that the absence of bold leadership is weakening international anti-corruption action and reducing pressure for reform globally.

“Corruption is not inevitable,” said François Valérian, Chair of Transparency International. He called on governments to strengthen democratic processes, independent oversight and civil society protections, warning of a growing disregard for international norms.

The organisation urged governments to renew political leadership on anti-corruption, protect civic space by ending attacks on journalists and NGOs, and close secrecy loopholes that allow corrupt money to move across borders through opaque ownership structures and professional gatekeepers.

In Europe, anti-corruption efforts have largely stalled over the past decade. Since 2012, 13 countries in western Europe and the EU have seen significant declines, while only seven have improved. Transparency International criticised the EU’s first Anti-Corruption Directive, agreed in December 2025, for lacking ambition and enforceability after key provisions were diluted by some member states.

The United States fell to its lowest-ever CPI score, amid concerns over actions targeting independent institutions and a weakening of enforcement against overseas corruption. Cuts to US funding for international civil society have also reduced global anti-corruption capacity, the report said.

High CPI scores do not guarantee immunity from corruption, the index noted, as some top-ranking countries have faced scrutiny for enabling cross-border money laundering. Switzerland (80) and Singapore (84) were cited as jurisdictions where financial systems have been linked to the movement of illicit funds.

Shrinking civic space remains a major concern. Over the past decade, governments in countries such as Georgia, Indonesia and Peru have introduced laws restricting NGO funding or operations, often accompanied by intimidation and smear campaigns. Transparency International said its chapters in Russia and Venezuela have been forced into exile due to repression.

The CPI covers 182 countries and territories, ranking them on a scale from zero (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). The global average score stands at 42, its lowest level in more than a decade, with more than two-thirds of countries scoring below 50.

Denmark topped the index for the eighth consecutive year with a score of 89, followed by Finland (88) and Singapore (84). The lowest-scoring countries include South Sudan (9), Somalia (9) and Venezuela (10), where corruption is compounded by instability and severely repressed civil societies.

Since 2012, 50 countries have recorded significant declines, including Türkiye, Hungary and Nicaragua, reflecting what Transparency International described as a structural weakening of integrity systems. By contrast, 31 countries, including Estonia, South Korea and Seychelles, have made sustained improvements, driven by reforms such as digitising public services, professionalising civil services and strengthening oversight institutions.